Tell Me a Story

Probably each one of us said it at some point when we were small children. Some of us said it almost every night. Some begged and pleaded. We laughed and giggled and screamed when our pleadings were granted.

Probably each one of us said it at some point when we were small children. Some of us said it almost every night. Some begged and pleaded. We laughed and giggled and screamed when our pleadings were granted.

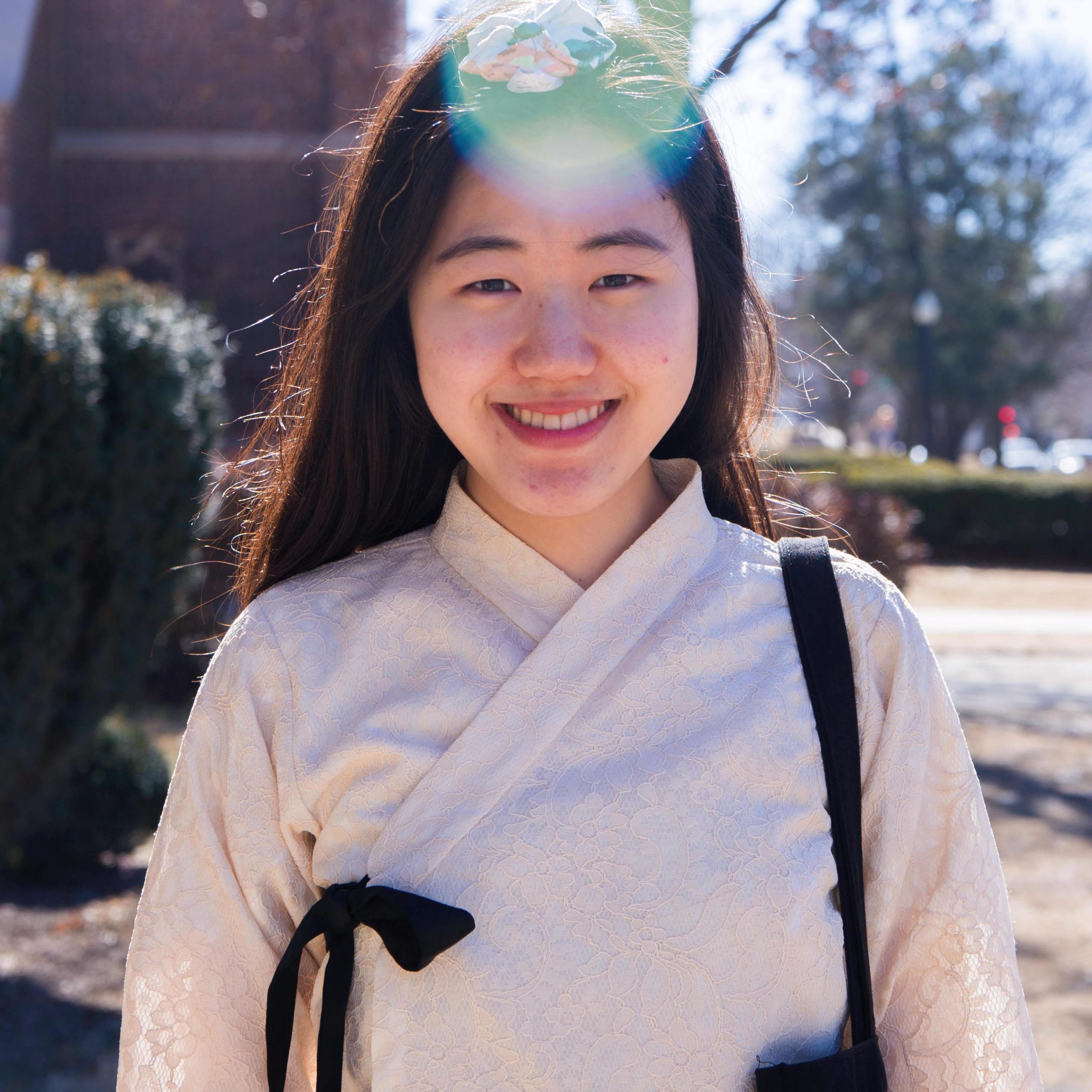

I’m a 21 year-old college student living in the Midwest. As the number of years I’ve spent in the States started to catch up to the number of years I’ve lived in Korea, my Korean-ness began to blur.

A musical journey from awkward childhood piano lessons to one night with Yiruma

What’s the worst part about living with a parent who has Alzheimer’s? Their repetition of words and phrases is a simple annoyance, the frailty of their human body is understandable, and their inability to feed themself is predictable.

One summer my wife and I toured half of the Silk Road through China. We were dating then. It was my first time traveling in a guided group—I had always traveled alone, cut off and trying for immersion, which might have been a way of reliving of my adoption.

On Wednesday, the day before I was scheduled to be induced, my parents arrived from New York with enough food to last us through Hurricane Katrina. They opened their suitcase, and it spilled out with cellophane packets of seaweed, an assortment of dried fish, varieties of ground rice powder, sesame seeds, and other ingredients for postpartum concoctions.

Growing up, my mother did not teach my sister and me about Korea. She did not teach us Korean. She did not feed us Korean food, and by middle school, my sister and I balked at her stinky jars of kimchee.

My grandmother was born in a year of famine, a hunger she never knew. A hunger she hungered for in missionary dreams. Starving in a heartland whose pulse, it seemed, had stopped; beat on in the hearts of those who could not return to it. A pulse in the burnt and sweated temples of bent-over coolies. A rhythm in the steps of my great-grandmother, deliberate and defiant dances at the Wahiawa Korean church. Her howls pierced the silence of the temple where the Japanese prayed, her neighbors in this country, her overlords in the other.

In popular culture, Asian Americans always seemed concerned with building bridges from old country to new country, first generation to second generation.

My father immigrated to America in the 1970s hoping to find better vocational opportunities. Back then, Korea was still in the process of recovering from the effects of war and the prospect of job mobility was limited. Dad was always a bit of a freethinker and I am pretty sure that even in his earlier years he had a desire to venture out of his homeland. After marrying my mother, they moved to Maryland and had three children. Eventually, through a culmination of decisions, my parents moved the family to Sunnyside, a city in New York. It was a perfect place for new immigrants since many of the residents had also just arrived from all different parts of the world including Turkey, Greece, and the Philippines.