A PTA Exposé, or, How My Dad Got His Cool On

The day after my father attended a PTA meeting at my high school, a teacher stopped me in the hall. “Your father is a remarkable man,” she said. I thought my father, who rarely went to PTA meetings, was an embarrassment. He was a Korean minister and also had an unglamorous as a translator for Voice of America’s Korean Service. I was a 1968 sullen eleventh-grader who smelled like patchouli and postured in homemade hippie clothes. By third period, I’d heard from two other teachers that my dad was cool. My father was smart, hardworking, short, his round head topped with thinning gray hair. He was sonorous on the pulpit and gullible for charity appeals that came in the mail. He wore black suits from J.C. Penney’s. A staunch anti-Communist, my dad, a Republican, believed in the necessity of the Vietnam War. My dad was not cool.

Though my father, Jacob Kim, came to America before the Korean War of 1950–1953, he remained a loyal nationalist, and gave presentations in church basements and Kiwanis clubs to garner support against Communist North Korea. In these community gatherings, he explained how the Soviets and Red Chinese had instigated North Korean aggression, and he stressed his belief that Communism was an evil to be feared.

I don’t remember exactly how my father mobilized to attend the PTA meeting, but the school had been buzzing with news that angry parents would protest the inclusion in a social studies class of Mao’s Little Red Book and Marx & Engel’s Communist Manifesto. Somehow my father heard this news, but he wouldn’t have mentioned it to me. In our family, with four kids at college, the remaining two of us were busy with our Beatle-manic Americanized lives, and we orbited distantly around our parents, together only on the occasions we landed at the dinner table or watched “Mission: Impossible” on TV. It’s typical that I wouldn’t have known that he attended the PTA meeting.

I don’t remember exactly how my father mobilized to attend the PTA meeting, but the school had been buzzing with news that angry parents would protest the inclusion in a social studies class of Mao’s Little Red Book and Marx & Engel’s Communist Manifesto. Somehow my father heard this news, but he wouldn’t have mentioned it to me. In our family, with four kids at college, the remaining two of us were busy with our Beatle-manic Americanized lives, and we orbited distantly around our parents, together only on the occasions we landed at the dinner table or watched “Mission: Impossible” on TV. It’s typical that I wouldn’t have known that he attended the PTA meeting.

At the end of that school day, the choral director mentioned my father’s wonderfulness, and I begged to know the whole story. And so the entire chorus heard about the PTA meeting, and much later, I learned additional details from my father.

In the crowded auditorium, outraged parents led a heated discussion to ban the Little Red Book and Communist Manifesto. They insisted that teaching these books would foster dangerous radicalism. The Social Studies and History teachers objected, but parents were adamant. Someone called for a vote. My father walked to the front of the auditorium. He would’ve still been in his suit and tie. I imagine that he used his preacher’s voice.

He told about the Korean War—an entire peninsula in such chaos that every Korean citizen, even those in the diaspora, was affected. He had not heard from his elderly parents in North Korea since before the war, and no longer expected to. One of his daughters, my third eldest sister, still lived in South Korea at that time. She was three when North Korea invaded, and our relatives fled Seoul by foot among mobs of refugees. My uncle pulled a handcart carrying my grandmother who’d had a stroke. After my sister tripped and was nearly crushed by the cart’s heavy wheels, she too rode atop their belongings. My father spoke about other relatives, a mother and her five-year-old daughter, who joined the panicked southbound masses. She lost hold of her daughter’s hand, and never saw her child again.

He told about the Korean War—an entire peninsula in such chaos that every Korean citizen, even those in the diaspora, was affected. He had not heard from his elderly parents in North Korea since before the war, and no longer expected to. One of his daughters, my third eldest sister, still lived in South Korea at that time. She was three when North Korea invaded, and our relatives fled Seoul by foot among mobs of refugees. My uncle pulled a handcart carrying my grandmother who’d had a stroke. After my sister tripped and was nearly crushed by the cart’s heavy wheels, she too rode atop their belongings. My father spoke about other relatives, a mother and her five-year-old daughter, who joined the panicked southbound masses. She lost hold of her daughter’s hand, and never saw her child again.

The Korean War never officially ended; a stalemate yields a tenuous peace threaded together by an armistice. The Communist threat was, and still is, a daily fact for South Koreans. My father, more than anyone else in that room, had the right to request that the teaching of these Communist books be banned—but if it came to a vote, he would vote “no.” Proudly naturalized just six years before, I’m certain my father cited the First Amendment, though freedom-of-speech protections for children in public schools would not become law until the following year.

As I recall this story, I remember an anecdote my mother told about my father as a young man. Sometime in the late 1930s in Korea, in the course of gleaning what information she could about him—a marriage prospect—she’d heard that once, he was so immersed in study that even his stern father couldn’t rouse his attention until he closed the two books spread on his desk. My father had been simultaneously reading the Bible and Karl Marx.

As I recall this story, I remember an anecdote my mother told about my father as a young man. Sometime in the late 1930s in Korea, in the course of gleaning what information she could about him—a marriage prospect—she’d heard that once, he was so immersed in study that even his stern father couldn’t rouse his attention until he closed the two books spread on his desk. My father had been simultaneously reading the Bible and Karl Marx.

At the PTA meeting, when my father said that reading Mao’s Little Red Book would not make us Communists, they got it. When he said that reading breeds intelligence and understanding, not treason, fear or hatred, they listened. No vote was taken. And my dad became cool, the teachers’ hero. That day gave me a glimpse into my father’s previously hidden history, and something great about his character. To us, his children, he had never once expressed the immense pain he’d experienced throughout the Korean War, but for the sake of education and the freedom to read, he did so to a crowd of other parents who wanted, and failed, to ban books from our classrooms.

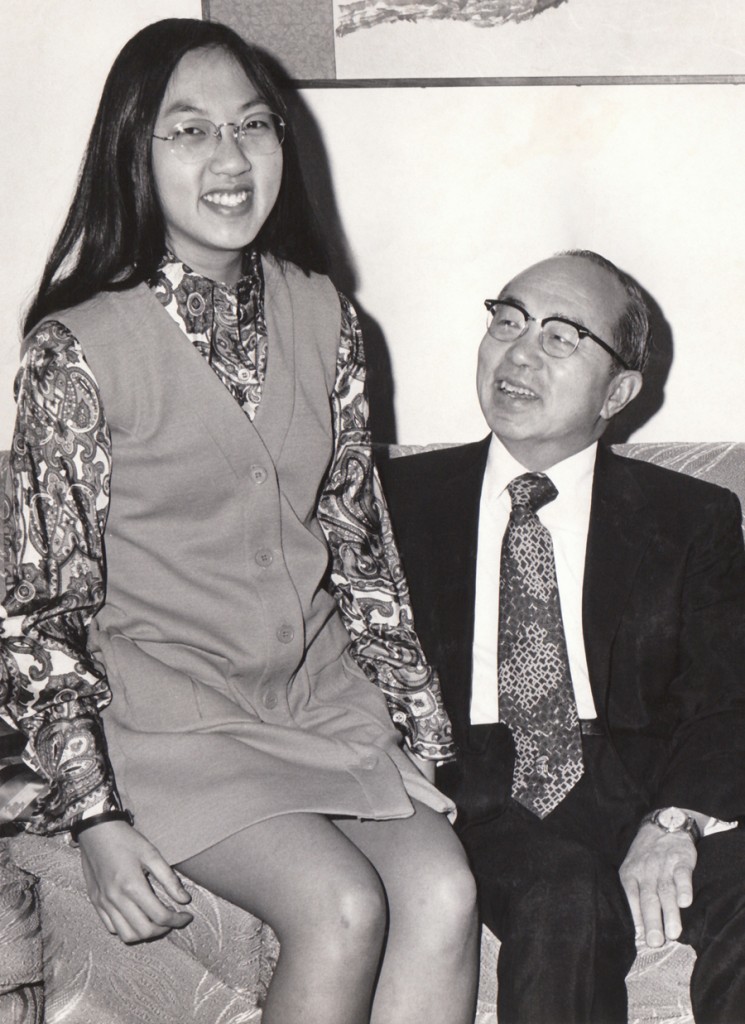

Vintage photos Courtesy Kim Family