I recently had the wonderful opportunity to read the book “0 Hour”, an autobiography written in Korean by Mr. Ki-Chang Kim (b. 1917). The book retells a captivating story of his experiences through much of the dominant events of 20th century Korea and later immigration to the U.S. The following is a summary introduction and translation of three portions of the book.

The immigration story of Mr. Kim and his family is itself remarkable, though in certain aspects perhaps familiar. But it is his entire life story that is absolutely compelling and, it seemed to me, too important not to be told. Among other things, his story made me reflect how many immigrants to the U.S. must have had such extraordinary experiences and how those personal backgrounds must have played a role in shaping the American experience not only for themselves and their families but the communities around them.

The story begins in 1945 in the area of Mokdan River (Mandarin: Mudanjiang), a city in Northeast China where a Korean diaspora community had formed during the Japanese occupation. Following the end of the Japanese occupation, Mr. Kim helps to organize a police force of the Korean community. When the Chinese People’s Army takes over the area, the police force is reorganized as a unit of the Chinese army and Mr. Kim becomes the leader of that battalion. As persecution of Christians increase in the area, he puts in action an incredible plan to relocate to Korea with several families in the church. I don’t want to give away the entire story (since I hope one day someone will translate the entire book), but with movement across the Korea-China border restricted, he is able to transport their savings in the form of hundreds of bushels of grain and beans to northern Korea. There he trades the goods, keeps a promise with Chinese army officials by sending military supplies back to China (with a note that he will follow later), then journeys on to southern Korea with his family and 700 sacks of fertilizer.

Chapters 7 and 35 of the book, which I have translated below, are toward the beginning and end of this first portion of Mr. Kim’s story.

The later part of the book recounts his experiences in South Korea–the Korean War and his escape from almost certain death after interrogation by North Korean command, his printing business and fortuitous experience with dry cleaning. The final three chapters, roughly half of which is translated below, describe his immigration to the U.S.

Expressions of Mr. Kim’s Christian faith are interspersed throughout the book. Fellow believers may see how God worked in his life through his faith. I think others will still see a man whose faith moved him and allowed him to carry on through seemingly impossible situations. – Hoon Lee

***

Chapter 7 Downfall from Greatness

“Who can restore a wrongful past. Water already flowed cannot turn the water wheel.”

The villagers and refugees looked like they had just survived a feverish illness. They had looked death in the face during the bombing spree and been on the receiving end of uncontrolled lootings of Soviet troops who had crashed in with tanks like angry waves.

It is late summer in this mountainside village but coldness fills the air when dusk settles.

Japanese soldiers showed up like uninvited visitors at the village, which was silent like a house after a funeral. The soldiers looked like they hadn’t eaten for days.

I sensed the fleetingness of life. Until recently their energy was boundless and their might appeared to reach the skies and now? They had come here to beg, having buried the anguish of a defeated country and swallowed the pride of the Grand Imperial Army.

“If you have food, clothing and medicine give it to us. We will pay.”

We were in a truly difficult position. The Soviet officer had commanded us not to help Japanese soldiers. There was peril either way, and even less could we respond to their request thinking of their brutal deeds against our nation.

The Japanese soldiers came to us Koreans out of trust or perhaps a sliver of hope.

It is said that a rat backed against a wall will bite a cat. Outside, Chinese villagers were watching our move. Some of us worried that Soviet troops would burn the village if they found out we helped Japanese soldiers. I searched out the village elder among the Chinese to discuss the matter. The village elder replied:

“There may be many more Japanese soldiers in the mountain. If we refuse they might attack us. Give them what they want and we will cooperate.”

We hurriedly cooked a cauldron of rice and gave it to the soldiers with kimchi, pickles and salt. The Chinese gave them steamed and dry bread. The Japanese soldiers bowed their heads repeatedly and hurried back into the mountain.

We cannot tie up our thoughts and emotions just on the memory of the past 36 years. We have to throw off the past nightmare. But worries about possible consequences lingered.

The drizzle turned to rain in the evening. It was just as I left the house to visit the cell group leader.

I stopped in my tracks upon seeing three Japanese soldiers with guns sheltering from the rain under the roof edge. They immediately looked down at the ground. A thought ran through my head. I went to the soldiers and asked, “Are you Koreans?” I saw tears in their pleading eyes.

The three soldiers put their guns on the ground and kneeled as if to ask for mercy. I looked carefully around and took the soldiers home. I signaled to those inside to be quiet and went to the cell group leader.

“Cell group leader, these are Korean student soldiers. If we don’t help them they will die. Please provide three sets of clothing for them. The uniform should be placed deep in the cauldron fire and the guns should be wrapped and hidden beneath the baggage in the storage area.”

The young former soldiers were still shivering with fear. We had made them into civilians but their shaved military heads could not be changed.

How many young Koreans are dying right now without anyone knowing? God helped these three. If we hadn’t taken them in they would have wandered the mountain with the Japanese soldiers and died or collapsed and taken prisoner.

The events of today cannot all be described in words. As I looked outside after supper the sun set behind the mountain and darkness and cold air settled in.

The young men were in deep sleep, snoring. They were unfortunate young Korean men wandering between life and death after having been conscripted into the army because they had no country.

God’s saving hands reached them at a perilous moment. Humans were created by God and those who believe in the story of creation will be protected.

August 18, we who came to the village as refugees felt like 10 days had been a year. We completed our preparation to leave the village. We had unknowingly come to a war zone instead of a refuge. We had experienced suffering and seen many deaths in this short life but the bombing at the village will remain forever in our memory.

We left, slow with emotion as we said our farewells to the village natives and church people and gave thanks for their hospitality and grace.

The three young men wanted to follow us but I turned them away warning of the danger of meeting Soviet soldiers in the town and telling them to help with the harvest and earn money to travel back home.

I prayed a prayer of thanksgiving to God.

“Father, thank you. Thank you for keeping us when the bombs showered down like rain. Not one person was harmed due to your protection. I know now without a doubt that you are alive and at work. Please be with us on the return journey. Amen.”

The party walked and rested along the mountain road and reached the Mokdan river around noon.

While we were waiting for a ferry boat a Soviet soldier came and played with our children. My brother-in-law translated that the soldier said they were very cute. He was pleased when my brother-in-law introduced our family and party and repeated “Horoshaw!”

The boat finally arrived. When we went down to board, the Soviet soldier helped people on board and waved his hand saying “ajinakoi” (see you again).

Near home, our party said reluctant farewells, finding it difficult to forget the miraculous experiences of surviving through a hellish war zone.

Coming home after more than 10 days, it felt as if I had been away for months. My mother-in-law and family members went to sleep tired after the long walk and tenseness.

I got up before dawn. The feeling of moving deeper into a labyrinth with no solution and no one to depend on kept me from sleep.

I left for the office after completing a prayer of thanksgiving for God’s overflowing love in this land stained with conflict, hatred and anger. During my absence the work of the group members had advanced greatly.

In this Mokan River city, Koreans lived in four districts—SuhJangAhn, HanYang, IpShin, and EkHa. SuhJangAhn and HanYang districts had the most Koreans and in total around 80,000 Koreans lived in the Mokdan city area. The wealthy and pro-Japanese lived in the New City district where the Japanese lived.

During the Japanese colonial period the ration system gave preference to the Japanese and pro-Japanese Koreans, who held red accountbooks. Next was the blue accountbook, held by Koreans and certain Chinese treated at the level of Koreans, which allowed the holder to receive a limited amount of rice, sugar and medicine. The last was the green accountbook held by all Chinese, which permitted no rice but corn, broomcorn and millet. The discrimination was severe, as sugar and medicine were difficult to come by for this last group.

The Chinese had to live with pent-up feelings, not being able to outwardly protest in the face of this humiliating treatment. Among Koreans there were police or military police assistants who mistreated Chinese people, and this fed their anger toward Koreans.

After the Japanese defeat, the Chinese recovered their land and Koreans became targets of the Chinese. It was easy to understand the desire to release their pent-up anguish, and who would be the target? The Japanese residents of the city had quickly left.

Korean residents lived in fear but had no solution. There was no official power or organization to protect us. Resolute determination and will are the only things that can solve the problems facing us. The only choice to survive in this anarchic situation is unity.

I called my brother-in-law Hong In-Pyo to translate our association’s strong statements of purpose into Russian. Next I gathered like-minded friends and discussed next steps but it is difficult to determine where to start. After long discussion the members decided it would be good to hear the wisdom of the elders.

There were several elders in the community who did not give in to the Japanese and had been active in the underground liberation movement. In particular, we decided to invite Paek Woo-Hak as well as several among church pastors and church elders. Mr. Paek was from Danchon in Korea’s Hamkyung province and had fought as a guerilla with Kim Il-Sung and Kim Jwa-Jin and had suffered after being apprehended by the Japanese army.

After consulting with 9 persons consisting of Mr. Paek, the pastors of the Presbyterian and Methodist churches and 6 local persons of influence, it was decided to split the organization with our association taking charge of security and training the young men for that purpose, and of establishing a network for communications.

The elders were to form a separate organization called the “Korean People’s Self Government Committee” and be responsible for government, education, recruiting, foreign relations and communications.

Next we decided to pursue the task of receiving guarantees of Koreans’ rights by contacting Chinese institutions and the office of the Soviet command.

We moved our office to the center of the SuhJangAhn district. The office consisted of a few desks and about a dozen chairs. Electricity and telephone was disconnected because the Japanese destroyed the generation and telephone facilities before they left. At night we continued our work with candles and gas lamps.

As time goes by Korean residents come with difficult, immediate problems that do not have immediate solutions. Soviet soldiers act in twos and threes, taking property from houses and harassing women.

The tide of history had completely turned. There is a reason for the enmity of the Chinese toward us. Past insults and oppression of the Chinese under the Japanese system had left a desire for vengeance that could not be turned back.

One day I went outside to see what the commotion was, and Chinese residents had tied a Korean man to a pole and were calling him names and urinating at him. He had been a Japanese frontman and had been caught by the Chinese.

I could do nothing but watch and my heart tore apart. Every incident like this helped establish among us a common goal.

Chapter 35. Escape

“It was not by human wisdom but God’s wisdom that we could carry out our given task without a hitch.”

“Success is not the product of chance. It is a tower built up over a long time.”

May 4, 1946, the little new sprouts have taken their fill of the warm noon sunshine and are beginning to shoot forth green leaves. The spring energy animating all creation fills the earth.

A month has passed since we arrived in Hamheung. Tomorrow we leave for South Chosun. I packed the luggage at the hotel and went to Tongyang Trading to take care of the matters outstanding with Director Cho. I went at lunch time because it seemed more natural to discuss the matters over lunch.

As we ate in a corner of the Chinese restaurant, I thanked him for the many ways in which he had helped. I searched for a way to bring up the topic of money. To leave for South Chosun it was critical to have South Chosun currency. I needed to obtain the cash by all means.

“Director Cho, I have one request. To do business with the traders in South Chosun I need South Chosun currency. As you probably know trades will be in cash because Tongchun is near the 38th parallel. It may be possible to barter the fertilizer but the counterparty may only take cash.”

“How much do you need? You know that the South Chosun currency is about 20% more expensive than the red currency here, right? If that is OK I will look into it. It will take a couple hours.”

“Please exchange for me five thousand South Chosun won.”

I handed him six thousand red won and told him I would be back in two hours. It seemed to me best to see the loading station where the fertilizer would be loaded on the ship tomorrow and inform the guard about tomorrow’s plans, so I headed to the security station at Heungnam dock.

The grand scale of Heungnam dock was as just I had heard. The size of the storage facility was much bigger than I had imagined, and the transporter machine operating through the warehouse roof and loading cargo on truck and ship was a sight to behold.

After looking on for a while at the equipment, I remembered that our nation’s blood and sweat had been taken to Japan through this dock and felt anger and frustration. During the occupation, because of our weak and incompetent people our goods and grain were freely taken to Japan, robbed because we could not keep what was ours.

On the way back from Heungnam dock I stopped by Hamheung station. For some reason the station is noisy with excitement. It was filled with soldiers in full uniform. I saw immediately that the uniform was familiar. It was the uniform I wore while I was a unit leader in China.

I searched and soon found officers that I had spent time with. They are surprised and glad to see me and grasp my hands.

We exchanged greetings and updates on how we’d been but I could not help feel like an outsider walking a very different path from them. I asked who their supreme commander was and, as expected, they told me it was Major Kim Kwang Hyup.

Major Kim was a member of the Yeonan faction who had fought in guerilla battles, studied political science and military studies in the Soviet Union, followed Kim Il-sung to Manchuria as an operative to train soldiers, and now had entered Pyongyang to as a supreme commander.

I parted with them and stopped by Tong Yang Trading to pick up the currency I had requested. Walking back to the hotel, I felt strange emotions swirling inside. All the events from Mokdan River to here flashed by my eyes. It was clear to me then that all of this was ordained and was God’s will. I had no reason or obligation to return to Mokdan River. I thanked God in prayer, feeling infinite mystery at the fact that all of the difficult moments had passed and now I could safely travel to South Chosun with my dear family.

“God does great things through people who quietly carry out the tasks given them.”

May 6, the fateful morning came. I am not a determinist but I believe that when difficult problems confront me I can only entrust myself to the almighty deity.

Mr. Pil came early in the morning. He says the ship must dock within three hours at the #3 dock at the Heungnam docks. I asked him to take my family to Suh-hojin by noon and ran to Suh-hojin first to meet Captain Bahng. I told Mr. Bahng to quickly dock the ship, showed the warehouse manager the permit to take the fertilizer from the warehouse, and requested permission to begin loading the ship.

Our ship finished preparations and docked at the Heungnam #3 dock before 10. As soon as the ship docks, the crane loads the fertilizer onto the ship. The workers organize the 700 bags of fertilizer and the work was finished in less than an hour.

After the fertilizer was loaded I took the ship back to Suh-hojin. The Pil brothers were waiting there for me with my family. I saw Evangelist Lee and Mrs. Pil as well. But I could not stay there long to say farewell to them. I had to get the ship on its way.

Staying here I had always felt anxious that somewhere somebody could report what we were doing. The feeling of danger and pressure that we must leave as soon as possible propelled me. I had my wife and daughter board the ship first.

I left for the coast guard station at Suh-hojin. The stationmaster looks happy to see me and asks the reason for my visit. He is very welcoming and warm to me since a few days ago.

I had figured out the reason for his kindness. Remembering his envious glances at my leather briefcase, I gave him the briefcase without hesitation. It would not be needed once I left this place. The stationmaster repeatedly thanked me.

I showed him the documents and told him I would have the ship depart immediately. In reply, the stationmaster says emphatically that ships cannot depart today. I felt my heart fall with a thud. I ran through in my head what might have gone wrong and asked him for the reason.

“Oh, nothing extraordinary but there are high waves today. The weather is treacherous so it is safer to depart tomorrow.”

I cried to myself, “No, we must depart today at all cost! How long have we waited for today?”

“Thank you for worrying about us. But we have a set schedule so we will undock the ship and if the waves are too severe we will return.”

At my insistence the stationmaster reluctantly gives permission.

“OK, give it a try. But don’t force it—it is dangerous.”

My heart ached as I said farewells to those who had come to see us off. But it was clear it would only get more difficult with time. Suppressing my emotion, I had the ship undock. I felt sorry looking at my wife, hiding in the cabin and quietly crying because she is not able even to say her goodbyes.

Chapter 49. Visions of a New Beginning

It was March 20, 1973, a few days before Easter. I called an important meeting regarding the kids’ and family’s future. I told them frankly that in today’s society ruled by privilege and class I wasn’t sure how to support a large family much less properly educate them. I told them of my decision to go to the new world of America to stake out a place for the family.

I was 58, looking on 60. In the past this would have been a time to retire from the front lines. The eldest three children finished college but four were in middle and high school. Providing tuition is extremely difficult. The conclusion is immigration.

I went to the U.S. embassy and applied for an entry visa. I submitted the documents and earnestly prayed to God. “Lord, give me one more opportunity and I will serve you to my utmost.” I felt that there would be no further opportunity if the visa was denied this time. Two hours later someone called “Kim Ki-Chang!” at the service window and I learned the visa had been issued. “God, I will never do anything against your will,” I repeated as I came out from the embassy. I went with my wife to a publisher that I had done business with for a long time. The publisher did not have its own printing facility and was using my plant.

The owner had stated at every opportunity, “I wish I could have this plant.” I ask him whether he has a mind to purchase the plant. He jumps on the proposal but ask me to wait while he gathers the funds.

I assigned the task of operating and selling the plant to my wife and, three days after receiving the visa, left on a plane to America.

I believed that fate is really God’s will and help will come if one lives according to God’s will.

Yet, on the plane I felt despondent. Why was I leaving as if being pursued? I wondered whether everyone leaving on a plane for the U.S. had the same feeling. A disordered and chaotic land but is this not my homeland? Leaving Korea I was low-spirited as if defeated.

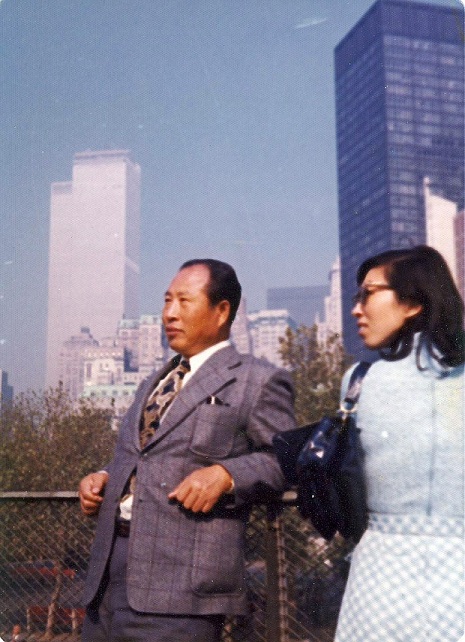

I arrived at New York Kennedy International Airport and, though this was not my first time, the airport felt strange and new to me. Nobody had invited me with a job or green card. My future was uncertain and my mind was heavy.

I had little luggage so the customs check was simple. Outside the airport my eldest daughter’s family of three greeted me and I went to their home in New Jersey which was an hour’s drive away. My daughter tells me that my granddaughter will sleep with her and I should use the child’s room. I felt I was imposing, for the place was a two bedroom rental.

I began to look for work the next day. Because I could not speak English I needed to go to Manhattan where there were many Koreans, and this made things difficult. There was a bus to Manhattan but you needed a car to get to the terminal and I had to depend on my daughter and her schedule for this.

After much thought I determined to leave her house and discussed with my daughter and son-in-law. My daughter told me, “Dad, you can’t do things by yourself because of language barrier. Why don’t you stay here for a while and return to Korea.”

After much thought I determined to leave her house and discussed with my daughter and son-in-law. My daughter told me, “Dad, you can’t do things by yourself because of language barrier. Why don’t you stay here for a while and return to Korea.”

I was stuck between a rock and a hard place but I couldn’t follow my daughter’s advice. A friend helped me get a room and I moved in with some kitchen utensils that my daughter prepared for me. I felt bad for my daughter but I couldn’t give up after coming all the way here.

The next day I started visiting people I know from Seoul. It was a struggle but if I had trouble finding the way I would make a phone call to make it to the destination. At that time it was still the initial phase of immigration for Koreans and there were not many who were comfortably settled. Most had difficulty with their businesses so that I didn’t feel comfortable bringing up my own problem.

There was a Yoon-chul Kim who had immigrated five years ago with his family and after initial difficulty was now relatively settled. He and I were good friends from having done Methodist church work together in Seoul.

When I felt alone I would visit his home and be welcomed with a bulgogi party and hospitality. I often welled up with tears when I saw his family and thought of my family back home.

Whenever I could I visited the home of Reverend Lee Jae-Eun, who had been sent to New York as a missionary. This is because I could meet people visiting from Korea. Reverend Lee’s place was always like an inn full of people passing through New York.

At the New York Methodist Church where Reverend Lee pastored there were many people who ran greengrocer stores selling vegetables and fruit. With what little remained of the money I brought from Korea I decided to open a greengrocer store. A printing business was out of the question because of my limited English. I had heard that areas with a Latin American population are good for the greengrocer business, and opened the store in a place called Union City across the Hudson,

I woke up at 3am to go to the fruit wholesale market but by the time I arrived at the store it was 10am which was too late to do business. I was forced to hire help but the paycheck took most of the profits.

In Union City there was a large population of immigrants from Cuba. There were many poor people like those refugees in Korea who had fled communist rule. Every street corner had a small store where the residents had IOU accounts and this made business difficult. They bought small amounts of vegetables but they hardly touched fruit which was more expensive.

Eventually I had to close the store having used up all the funds I had brought from Korea.

Starting the next day I went around visiting printing presses telling them of my printing experience and asking for employment. These were American printers that I was meeting for the first time. Many times owners would tell me they would consult their lawyer, but when I went back they told me they couldn’t hire me because I didn’t have a green card.

One day I visited a small printing press. After listening to my story the owner says he will help. “It seems you are in a bind. Let’s try working this out together. If you prepare the papers I will sign.”

I was so thankful I went straight to the INS to obtain all the required forms and submitted an application for employment authorization to the Labor Department with the help of Rev. Kim Hae-Jong. The unemployment rate was high in the U.S. at that time so it was difficult for foreigners without special skills to obtain a work permit.

To address that concern I carefully included all relevant information and submitted the application after adding an explanation that I was essential to obtaining printing orders from the Korean businesses in Manhattan.

Chapter 51. Starting Anew

“One must live life steadfastly, knowing that time will pass like flowing water and everything will come and go.”

“Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen. For by it the elders obtained a good report.” <Hebrews 11:1-2>

“Fight the good fight of the faith. Take hold of the eternal life to which you were called when you made your good confession in the presence of many witnesses.” <1 Timothy 6:12>

October 25, 1975, finally as dreamed my 8 family members arrived in the U.S. Tears welled up when I saw my family for the first time in over two years. I just stood there hugging them, suppressing my emotions.

I saw my wife’s gaunt face and thought about how she must have endured with patience waiting with the kids. I also felt admiration that she had taken care of them by herself.

The kids’ faces are bright. They seem to be happy to be reunited with their father in a land of freedom and dreams.

We left the terminal in two cars loaded with luggage and headed home.

The next day was a Sunday so our entire family went to church. The pastor introduced our family and the church members looked at us admiringly. At the time, it was understood that having a family labor force was a great asset.

My second daughter found a job at an architectural firm after a few days and began to commute to work, and soon the other children found their jobs and began to work. But there was a problem. The work was all in the direction of Manhattan so it was a difficult commute transferring between the bus and the subway, and if any of them left the office late the entire family was worried.

I thought of different solutions and, two months after the family arrived, decided to move to a place called Rego Park in Queens, New York.

A church member asked me to work at a larger dry cleaner’s so I switched my work to there. At that time there were not many Koreans with dry cleaning skills so the Korean owners hired African Americans or Latin Americans and there were often difficulties with customers’ clothes being ruined.

My profession is the printing business and I received my green card by virtue of my thirty years of experience in printing. Now I was able to stake out my life in the U.S. thanks to my stint at dry cleaning in Korea. I realized that none of this occurred by chance. To rescue me God had allowed me to gain experience in dry cleaning.

Without God’s grace it was impossible to have lived through the myriad difficulties and have a good job in the dry cleaning business.

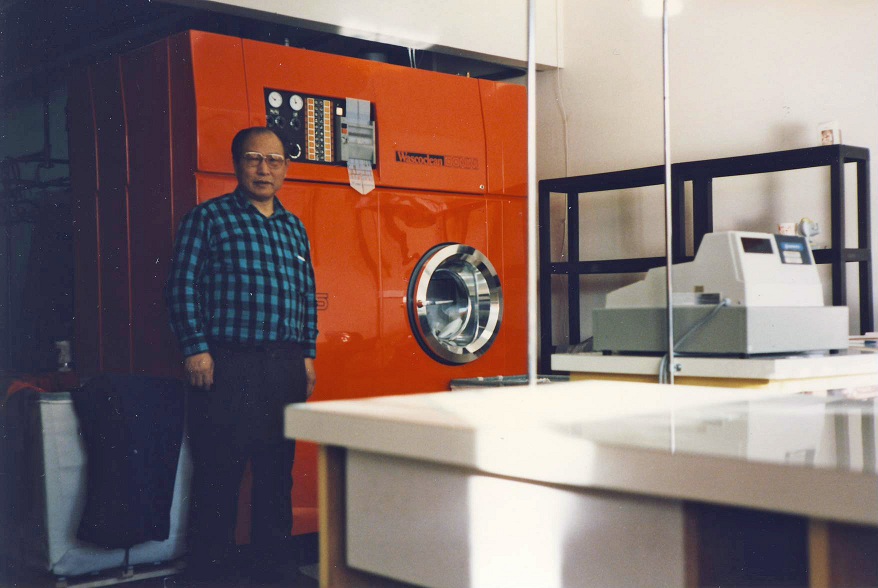

July 1977, I took over the dry cleaning business. It was a large business in which 11 people had worked but we did not have to worry much because our family was large. Our school age kids also helped out in the afternoon. Our family could feel our good blessing steadily increase after taking over the dry cleaner’s.

[Chapter continues with Mr. Kim recounting his operation of the business and his serving the church at New York Methodist Church, the division and litigation that that church experienced, and the revival of that church. He closes the chapter, the last of the book, thanking God for giving him vivid memory so that he could record this book as if events of 50 years ago took place yesterday.]